in category Golang Programming

How I organize packages in Go

Structuring the source code can be as challenging as writing it. There are many approaches to do so. Bad decisions can be painful and refactoring can be very time-consuming. On the other hand, it’s almost impossible to perfectly design your application at the beginning. What’s more, some solutions may work at some application’s size and should the application develop over time. Our software should grow with the problem it’s solving.

I mostly develop microservices and this architecture fits great to my needs. Projects with much more domain in it or more infrastructure applications may require a different approach. Let me know in the comments below what’s your design and where it makes sense the most.

Packages and its dependencies

When it comes to developing domain services, it’s useful to split the service by domain’s components. Every component should be independent and, in theory, be able to be extracted to an external service if needed. What does it mean and how to achieve that?

Let’s assume that we have a service which handles everything related to placing orders like sending an email confirmation, saving information to a database, connecting with a payment provider etc. Every of the package should have a name which clearly says what’s for and compatible with the naming standard.

This is only an example of a project where we have 3 packages: confemails, payproviders and warehouse. Names should be short and self-explaining.

Every of the package has his own Setup() function. The function accepts only bare requirements to be able to work correctly and be able to communicate with the world outside of the package. For example, if the package exposes an HTTP endpoint, the Setup() function accepts an HTTP router like mux Router. When you’re package requires access to the database then Setup() function accepts sql.DB as well. Of course, the package can need another package, too.

Inside of the package

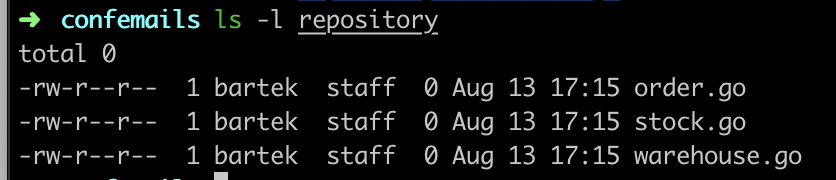

When we know the external dependencies of our module, we should focus on how to organize the code inside of it. At the very beginning, the package contains the following files:

- setup.go - where the Setup() function leaves

- service.go - it’s a place where the logic has its place

- repository.go - we need to fetch/save the information somewhere

The Setup() function is responsible for building every building block of the module that is: services, repositories, registering event handlers or HTTP handlers and so on. This is an example of real production code which uses this approach.

func Setup(router *mux.Router, httpClient httpGetter, auth jwtmiddleware.Authorization, logger logger) {

h := httpHandler{

logger: logger,

requestClaims: jwtutil.NewHTTPRequestClaims(client),

service: service{client: httpClient},

}

auth.CreateRoute("/v1/lastAnswerTime", h.proxyRequest, http.MethodGet)

}As you can see, it builds a JWT middleware, a service which handles all the business logic (and where a logger is passed) and registers the HTTP handler. Thanks to that, the module is very independent and (in theory) can be moved out to a separate microservice without much work. And at the end, all of the packages are configured in the main function.

Sometimes, a few handlers or repositories are needed. For example, some information can be stored in a database and then sent via an event to a different part of your platform. Keeping only one repository with a method like saveToDb() isn’t that handy at all. All of elements like that are split by the functionality: repository_order.go or service_user.go. If there are more than 3 types of the object, there are moved to a separate subfolder.

Testing

When it comes to testing, I stick to a few rules. Firstly, use interfaces in the Setup() function. Those interfaces should be as small as possible. In the example above, there’s httpGetter interface. The interface has only Get() function in it.

type httpGetter interface {

Get(url string) (resp *http.Response, err error)

}Thank’s to that, I only have to mock only 1 method. The interface is always as close to its usage as possible.

Secondly, try to write fewer tests which will cover more code at the same time. There’s no sense to write a test for every repository or service separately. For every domain decision/operation, one successful and one failed test should be sufficient and cover about 80% of the code. Sometimes, there is some critical part of the application. Then, this part can be covered by separate test cases.

Finally, write tests in separate package suffixed with _test and put it inside of the module. It will help to keep everything in one place.

When you want to test the whole application, prepare every dependency in the setup() function next to the main function. It’ll give you the same setup for both production and test environments that can save you some bugs. Tests should reuse the setup() function and mock only those dependencies which aren’t easy to mock (like external APIs).

Summary

All the rest files like .travis.yaml etc are kept in the project root. It gives me a clear view of the whole project. I know where to look for the domain files, where infrastructure-related files are and there aren’t mixed. Otherwise, the main folder of the project would become a mess.

As I said in the introduction, I know that all of the projects won’t benefit from this way of organizing project but smaller applications like microservices can find it very useful.

Buy me a coffeeTags:

#golang

Buy me a coffeeTags:

#golang